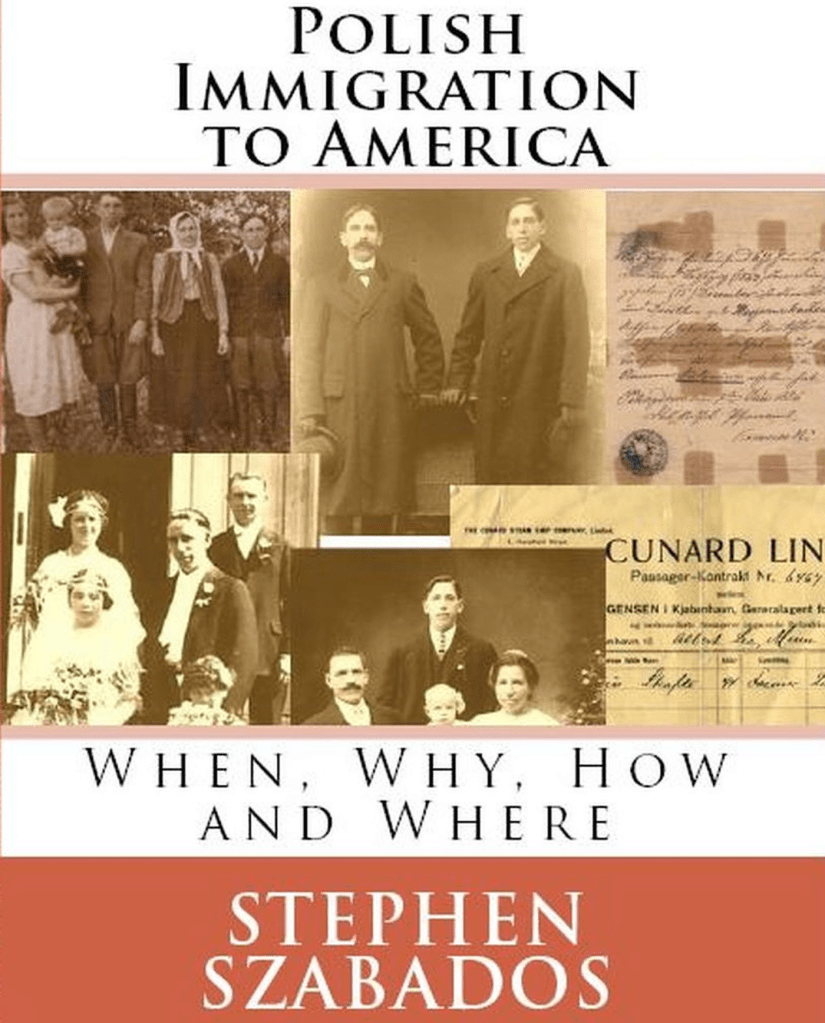

Now is a time for us to celebrate our Polish heritage, and the story of our immigrant ancestors is the foundation of that Heritage.

I spent much of my early life with my Polish grandparents, and my genealogy research began because I wanted to learn more about their lives in Poland. The success of my early research shifted my goal to saving my discoveries for my children and grandchildren. I decided that I could best do this by compiling a written Family History that is a narrative and contains stories, photos, maps, and documents. I envision my family histories as greatly enhanced scrapbooks focusing on the narratives that explain the images, maps, and documents. I also describe my family histories as collections of summaries of individual ancestors that I have organized into one large document.

I started my research by collecting family photos, family papers, and oral history and quickly moved on to census, naturalization, passenger, and marriage records. These records led me to identify their birthplace and more documents for my Polish ancestors.

I found accounts that described Polish life in the places where they lived. I also found vintage pictures of the town, church, and homes. Polish relatives also gave me copies of the family members who stayed. I included all of this information in my family histories as it was related to my ancestors.

As I compiled my family history, these steps started to bring my grandparents and their ancestors back to life. Note that this process did not happen quickly or with one significant revelation. Instead, the vision of my ancestors came together one piece at a time and over many years.

Capturing the immigration story is an essential step in honoring our Polish Heritage. Envisioning the challenges that our Polish immigrants faced on their journey to America is another critical aspect. Identify the port they left and the size of the ship. Review the passenger manifest. How was life on board the ship? What was their destination? Link the information in the documents and find the stories.

It was not easy to immigrate to America. Leaving home was a very emotional decision. Those who left saw immigration as their only chance to escape the poverty of their life in Poland. Not only were they leaving their family and friends, but the emigrants were leaving their beloved homeland. Some may have been excited about emigrating, but there was also fear of the unknown — most left home with tears in their eyes.

Try to describe their lives in America. Look through old pictures in family albums and also history books of the local area and neighborhoods. Pictures of their homes, neighborhood, and their church are vital. Next, identify where they worked because this would have been a significant part of their lives. Finally, look at their overall experience in America. How did they enjoy their new life? Did they do anything outside of work? Did they have a hobby? Were they active in a fraternal group? Did you find pictures of family gatherings? How was their life here better than what they would have had in Poland?

We will not find answers to most of these questions. However, asking the questions and doing the research will give us a perspective of what our ancestors may have experienced and better understand their character and our Polish Heritage.

Our immigrant ancestors were heroes, and they are the foundation of our roots in the United States. Do not underestimate their contributions. They may have left us some material wealth, but their most significant contribution is their role in the factories and farms of the United States. Their names will not appear in history books, but their efforts impacted American history, and without their sacrifices, our country would not have developed as it did. Their lives were the building blocks in the growth of their new country, and their immigration influenced the quality of our lives today in the United States. Remember that they made many sacrifices for you and helped build the United States.

Be patient. Keep asking questions and looking for records and stories. Then, write down the stories and organize them in family histories.

Save the stories for your future generations

Have fun, and enjoy your Polish Heritage.